“Mos Eisley Spaceport. You will never find a more wretched hive of scum and villainy. We must be cautious.” ―Obi-Wan Kenobi

One of the favored scenes of adventure stories, whether they exist in film or in print is the lawless city. Mos Eisley in Star Wars, Crobuzon in Perdido Street Station, the Narrows in the Dark Knight, Haven from the Hawk and Fisher books, even the city from the movie Streets of Fire. Heck, it’s a tv trope: Wretched Hive.

It’s a city where there is no control, no support, just the darkest parts of the human spirit made flesh and given free range to roam its grimy streets. There may be a distant government, or simply an uncaring one, but it’s a blank canvas on which characters are allowed to have adventures they wouldn’t be able to have in our hum-drum normal reality.

Surely those places don’t exist in the real world, right?

|

| Credit |

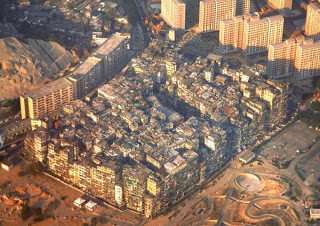

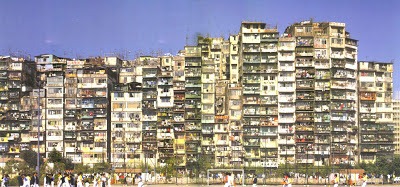

Well, maybe they do. Take Kowloon Walled City, approximately two blocks (6.5 acres) of densely populated, 10-14 stories of rickety ungoverned teeming cityscape in Hong Kong. Originally when the British extended Hong Kong Territory in 1898 the small walled fort and its population of roughly 700 people was excluded from the surrounding area. The fort would change hands many times over the next couple of years as the British tried to take it back, then left it to itself, as the Japanese invaded during WWII (demolishing part of its walls), and then China tried to retake it back after their surrender. Refugees poured into the small area and, after failing to drive them out in 1948, the British decided to let them be.

This meant that inside of the British colony there was a small part that nominally belonged to the Chinese but was practically ungoverned. It became a city on to itself filled with approximately 33,000 people- giving it a population density of 3,249,000 per square mile. Just to put that number in perspective, Hong Kong was considered one of the most densely populated places on earth at that time with a population density of only 17,000 people per square mile.

|

| Credit |

Needless to say, crime flourished. Triads gangs ran the place for a time, filling it with drugs, gambling, and prostitutes. But it was also filled with doctors and dentists who, although skilled, preferred not to pay the high prices that the Hong Kong government required for licenses. Charities and churches filtered in, offering food and support to the people there.

|

| Credit |

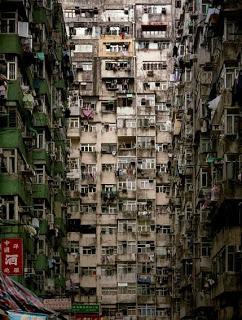

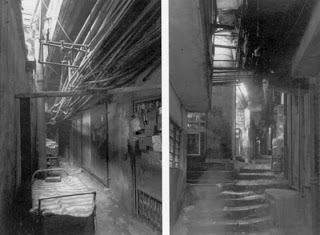

Despite it all, or perhaps because of it, the city grew. Almost all of the buildings grew to at least ten stories tall, although the nearby Kai Tak Airport kept them from growing more than fourteen. Alleys were narrow and, as buildings grew outwards as they went upward, rarely saw much light. Most people traversed the city not by these three-six feet wide alleys but by an informal network of ladders, stairways, and passages that stretched from roof to roof and from upper story to upper story. It was fully possible that one could travel the city from one direction to the other without ever having to touch the ground.

|

| Credit |

Without access to a government to provide normal city services Kowloon made its own way. The inhabitants sank some 70 wells in and around the city, pumping it up to rooftops and using that water pressure to supply to a mess of families and homes. Electricity was originally stolen from the mains, likely by Hongkong Electric employees who lived in the city, although a fire in the late 1970’s brought in more reputable means of energy.

Communities formed between neighbors, just as they do everywhere, and as the gangs were pushed out by heavy police raids- and not a little support from mostly law-abiding members of the city- these little groups grew. Enterprising individuals sold food and goods at cheaper prices than the rest of the colony, or collected waste from chamber pots and took out trash.

All the same, both the Chinese government and the British saw Kowloon as a blight on their landscape and determined to demolish it. In 1987 they announced their decision and slowly began to move out the residents and businesses, offering compensation to those they forced to move. Many of those communities banded together to try to protest the eviction, but between November 1991 and July 1992 they were forced to leave the city and demolition began in earnest.

By the end of 1994 the city was gone and construction had started on the park that now sits in its place, the only remainder of the teeming mass of humanity that had once flourished there, lawless, free, and with all of the negatives, pluses, and stories that come with the darkness of narrow alleys and harrowed hearts.

|

| Credit |

This was an excelent description of the Kowloon City, I specially liked how you ended it, great entry!